Date of Publication:

29 October 2025

Nils LANG

Waseda University, Japan

Editorial Note(s)

This work was conditionally accepted to and presented at the 2025 Youth Symposium: The Intersection of Research, Civil Society, and Young People in East Asia, held at the University of Tokyo from 22 to 24 August 2025. It is published in Anchor Archives solely as part of the symposium proceedings and is not an Anchor article. The Editorial Team is not responsible for spelling and language errors of the article and made only minimal formatting changes to the article to ensure it aligns with the style of the symposium proceedings. The author notes that this is a work-in-progress draft and it should not be cited.

Abstract

China has achieved dominance in the rare earth industry. Which Industrial Policies were used by the CCP to enable this dominance? This essay will take a close look at the industrial policies that enabled China to become dominant and essential in the global supply chain. I will examine the role of state-driven policies across three major segments: upstream extraction, midstream processing, and downstream application. While the focus lies with the first two, a growing dominance in the third capability has been observed in recent years.

1 Introduction

Rare Earths (RE) or Rare Earth Elements (REE) are essential for the High-Tech industry, renewable energy and the defense industry. This group of 17 chemical elements exhibit unique properties as they are magnetic, phosphorescent (light-emitting), and have catalytic properties. These attributes allow them to perform functions that are difficult to achieve with other materials, especially at the same weight. In High-Tech devices (smartphones, computers, camera lenses etc.) REEs enable smaller sizes, increased efficiency, and better performance. In the field of Green-Tech they are the basis used to create strong, lightweight permanent magnets found in electric vehicle (EV) motors and wind turbine generators. Over the last three decades China has become the major supplier for industries demanding RE products all around the world.

2 Rare Earth Supply Chain: An Overview

2.1 Definition

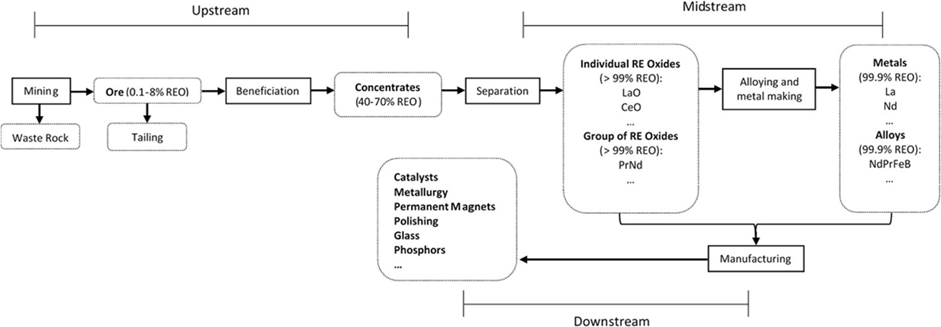

Upstream or primary products are RE ores and concentrates. Midstream products are defined as separated Rare Earth Oxides (REO), metals, and alloys. The downstream sector can generally be understood as the sum of users of midstream products for the manufacturing of Rare Earth-containing products. For this essay I wil limit the scope of the downstream sector to only be about permanent magnets containing Rare Earths. In future research this could also be extended to include EVs, Wind Turbines, Smartphones, Fighter Jets etc.

2.2 Geology of Rare Earths

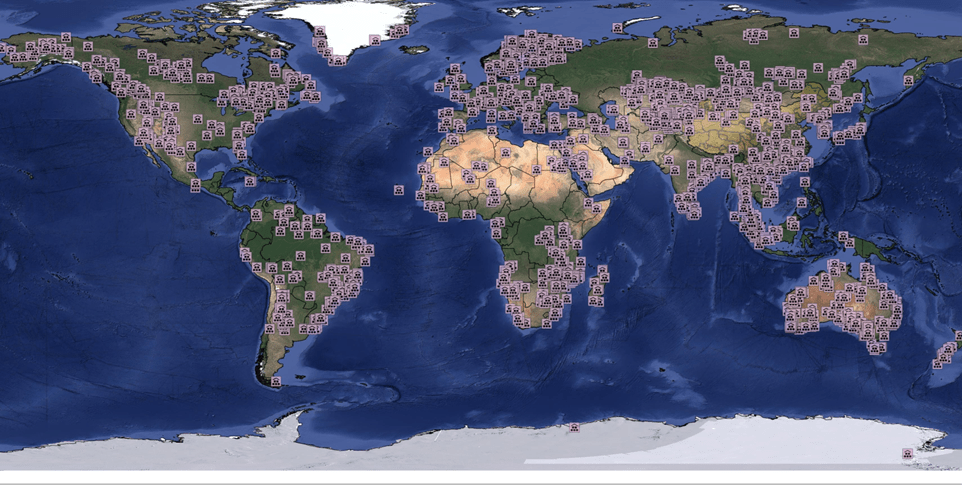

Rare Earths are not truly ”rare” in geological abundance, but they are rarely found in economically viable concentrations. While they exist all around the world, finding deposits that are concentrated enough to be mined profitably is challenging. Ore deposits tightly bonded together and in varying proportions and mixes of REEs. Economic viability has also been shifting over recent decades, since the market is under the influence of highly volatile prices, which are heavily influenced by geopolitical developments.

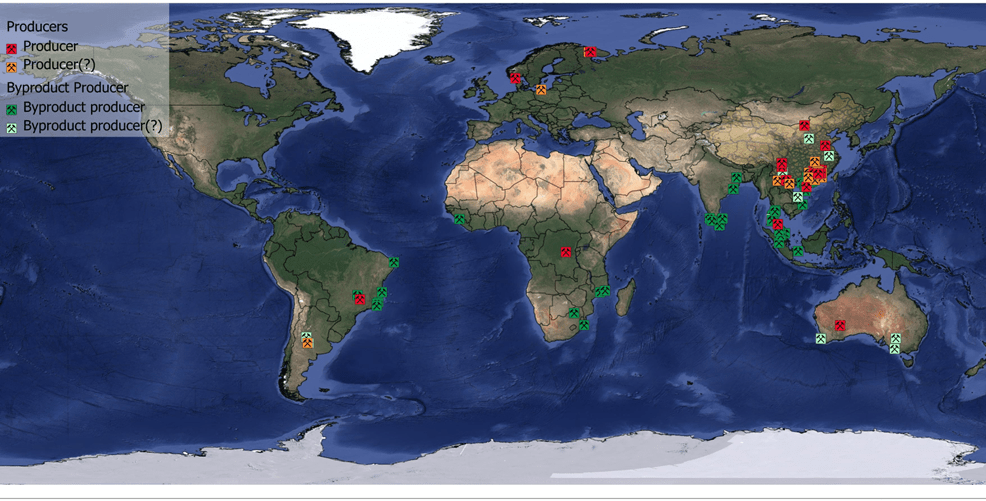

Figure 1: Known Deposits of Rare Earths worldwide [6]

2.3 Upstream Extraction

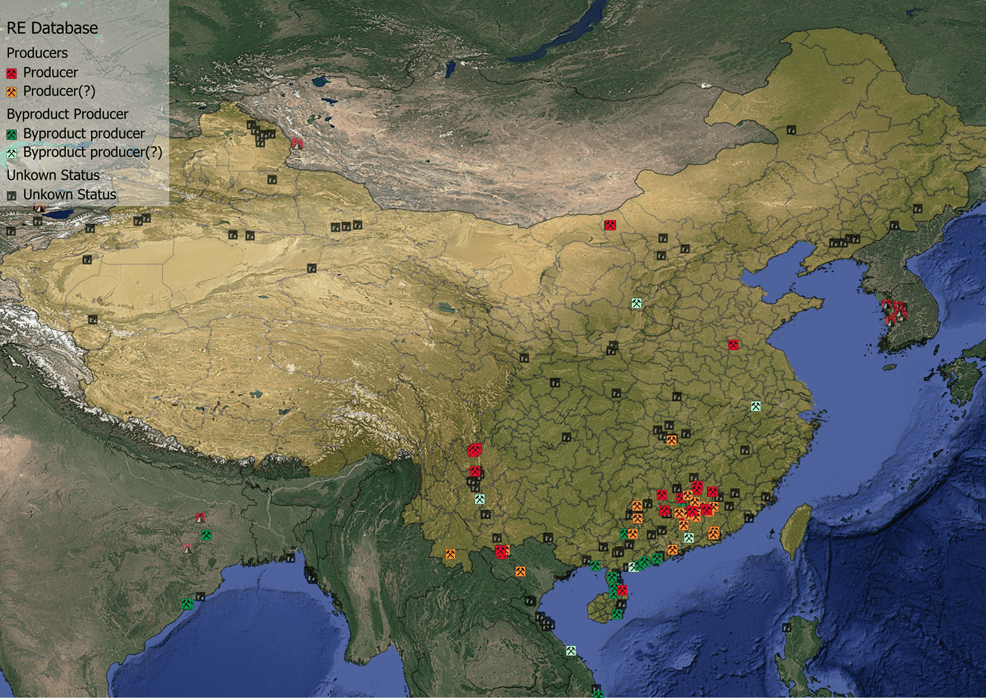

The first step in the supply chain is the extraction of raw unprocessed REEs from the earth. They are extracted from the earth using acid in an environmentally damaging extraction process. In the 1980s this lead to many western nations off-shoring the mining operations, which China happily on-shored. Today more then 90% of yearly global output of refined metals used for rare earth magnets comes from China. [2] . Deposits in the North of China have more Light REEs, with a relatively large proportion of the lower-valued lanthanum and cerium elements. These are frequently stockpiled at the mines there because market prices are consistently low. In the South the concentration of Heavy REEs, used in permanent magnets is higher. The location and distribution of RE mines in China can be found in Figure 2.[a]

Figure 2: Active REE producing and as byproduct producing mines in China [6]

2.4 Midstream Processing and Separation

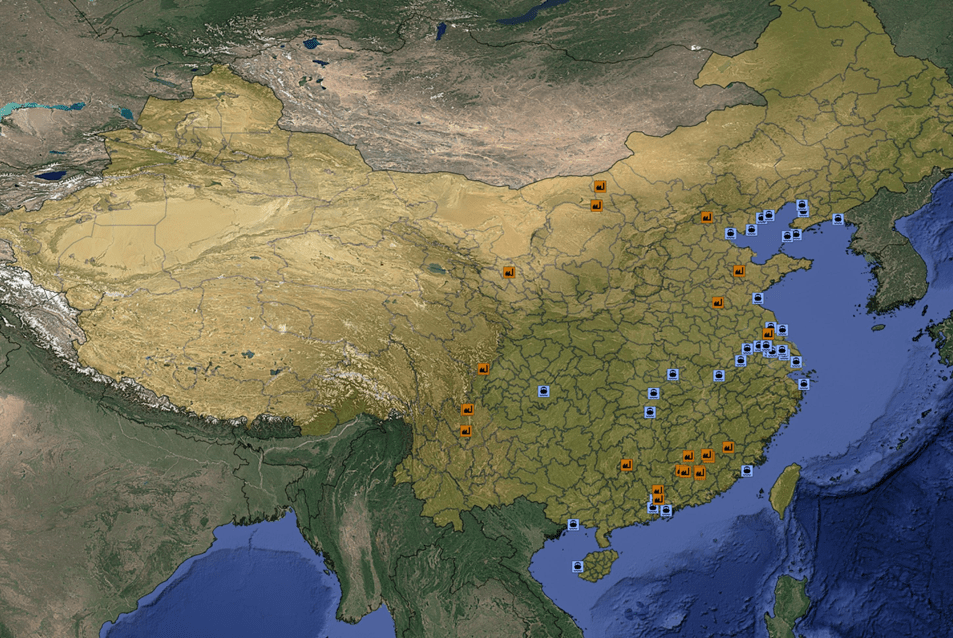

Separation of the different REEs is a highly energy intensive process and require a lot of know-how, since the REEs are quite similar in their chemical structure. [4] While there are different fundamental approaches on how to arrive at > 99% pure Rare Earth Oxides, they all generate a lot of waste water and rely on cheap energy to be profitable. After separation the resulting oxides and salts are then converted into metals or alloys. High-Purity metals are commonly produced by Metallothermic Reduction. For most industry applications in the downstream an alloy, a mixture of REEs and other metals (aluminum, steel, iron etc.), is needed.

Figure 3: Active midstream RE Processing locations and major ports exporting metals in China [5]

2.5 Downstream Manufacturing

While there are other alloys being produced and used in industrial contexts, in general the most important B2B market is that of permanent magnets made with REE. The two type of permanent magnets, which are most notable are Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) and Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) magnets. For both of these rare earth magnets there are two methods of producing sintered and bonded magnets requiring high technical skill and knowledge. China dominates both sintered and bonded rare earth magnet manufacturing, controlling a vast majority of global production.

Figure 4: Definition of the different Segments in the Supply Chain. Copyright: [7]

3 Chinas Rare Earth Industry

In this section I will give an overview of the most important and influential policies taken by the CCP with respect to the RE Industry. Notably policies by other countries are ignored, but in general other countries did not pay attention to the industry until 2011, when there was a first unofficial embargo by China towards Japan and a renewed interest in recent years due the second Trump administration bringing up the topic consistently and the rare earth deal with Ukraine.

3.1 Beginnings of the RE Industry

The technological understanding of extraction, separation, smelting, and further processing of RE minerals started being developed in China in the late 1950. Even before the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, China started exporting mixed RE chlorides in 1973. [7] [11] While the volume of exports in the period from 1973 to 1978 was merely 150 tonnes, the volume steadily and drastically increased over the following years. [7] At the beginning of the 1980s RE trade products between China and Japan were primary mixed RE materials, since Japan still had a strong separation capacity with low cost. [7] At the same time the USA started increasing its imports of RE chlorides from China starting in the early 1980s. By 1985, Chinas capacity for producing mixed RE chlorides and oxides was approximately 10,000 t. [11]

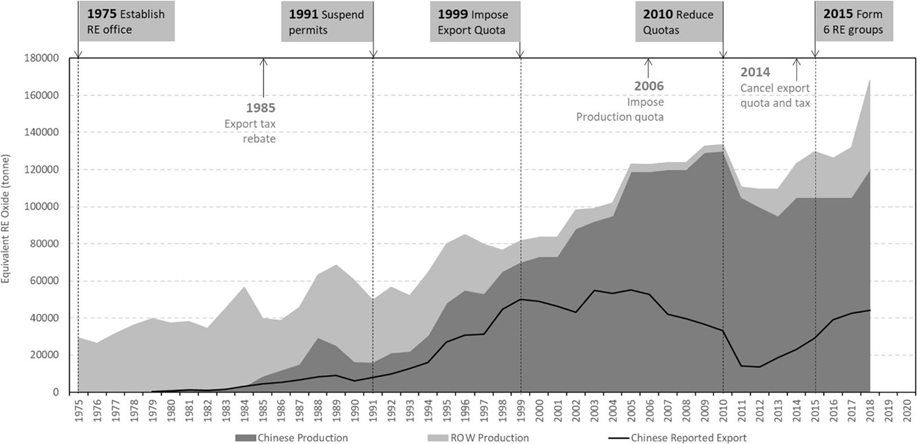

Figure 5: Chinese and Rest-of-World Mine Production of Rare Earths and Chinese Exports. [12] Copyright: [6]

3.2 Industrial Policy for Development

Before the establishment of the ”National Rare Earth Development and Application Leading Group” (RE office) in 1975, there was no government agency overseeing the industry. In the period until 1990 Chinas RE policy was focused on supporting the development of the RE mining industry into maturity. Domestic consumption alone was not sufficient to support much growth in the industry. To develop the industry and amass foreign reserves, China attempted to expand the export of RE products. In 1985, RE exports became eligible for export-tax reimbursement so that RE firms were being payed back the export-product tax or the added-value tax. [9] This lead to a rapid expansion of production capacity, which can be seen in Figure 3. From 1985 to 1990 Chinas RE minerals production doubled from 8500 t of REO to 16,500.

[11] In the early 1990s China started restricting foreign investment especially in the upstream sector. This meant that all foreign investment in the RE industry had to be approved by the RE office. Foreign investors started having restricted access to RE exploration, mining, beneficiation, smelting, and separation. Any projects that damaged the environment and natural resources, which mining inherently is, could have no foreign investment involved. Beginning in 1991 exploration and mining licenses were frequently suspended and China only renewed licenses for qualified firms and only issued new licenses for government-involved exploration. [7]

3.3 Investment Policies

In 1991 the Chinese State increased their grip over the RE Sector by categorizing ionic clays as “national protective exploitation minerals” that should be regulated by the central government for all of the stages of the supply chain. The RE office was gonna be in charge of middle to long-term ionic clay resource development and planning. State-owned mining enterprises approved by the RE office had priority to develop RE ionic clays. Enterprises with collective ownership could only mine small and low-grade reserves. Private enterprises were not allowed to participate in the industry at all. The RE office would develop production plans for ionic-type RE concentrate and smelting products. Collective-owned and privately owned firms could not be involved in ionic-type RE separation and smelting. The RE office also planed all of the domestic trade. [8] This increase in control and reduced competition surprisingly did not lead to less production though. [7]

Running parallel to the growth of the industry, there was also a push for a consolidation of the states control over the whole supply chain.

3.4 Export Quota

Before mentioned export reimbursement on RE ores, metals, and oxides were in place until 2004. Then they were gradually reduced and finally cancelled. First it was decreased to 5 Percent and then completely cancelled in 2005. From 2007 China started imposing taxes. Therefore the upstream sector saw slower growth, but the midstream and downstream industry saw accelerated growth due to less restriction on exports once the rare earths were processed. In 1999 China introduced an export quota, which by the market power of China at that point became the most important number for the international RE market. Starting in 2005 the export quota was continuously reduced year by year. [10] During the time the export quota was in place different parts of the Chinese state were in control of setting the quota and distribution of licenses to export. From 1999 to 2002 the quota was determined by the State Development and Planning Commission (formerly only State Planning Commission). Distribution of the determined quota was organized by the State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) and the MOFTEC (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Commerce) issued the licenses. After 2003 the SETC and MOFTEC were abolished and the Ministry of Commerce (MOC) became responsible for both the issuance and distribution of export licenses. Different export quotas were set for domestic rare-earth producers and for joint-venture RE producers. Joint-venture RE companies were allowed to export their own products under a licensing system. One can see the chinese governments intention to develop the downstream in the way the export quota developed over time. [10] After a dispute with the World Trade Organization filed by the EU, Japan and the US, China cancelled its export quota in 2014 quota and export tax on RE products in 2015. Thereafter, firms did not need approval for exports and could acquire licenses based on trading contracts. [13]

3.5 Production Quota

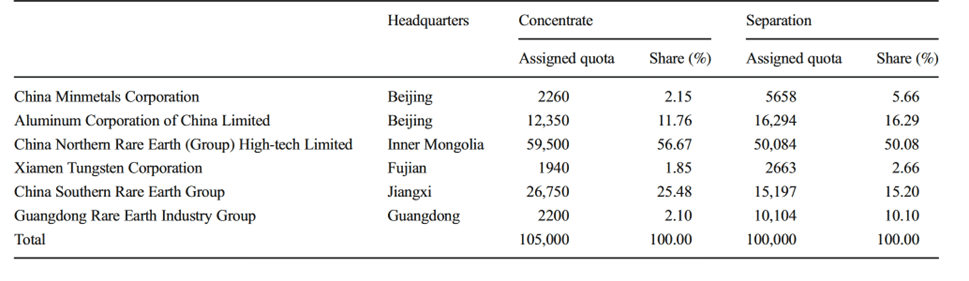

The export quota successfully helped keep prices in Chinas domestic market low and increased the incentive to have companies in the midstream and downstream produce in China itself. But there was also the worry in the Chinese Government of too much rare earths being mined and taken out of the ground. At least that was the official reason on why foreign investments were prohibited from investing in mining, smelting or separation projects except for joint-ventures. Since the early 1990s the RE office was under the administration of the Ministry of Land and Resources (MLR), which started issuing production quota for all of China as well as the individual provinces. These were issued in metric tons of rare-earth-oxide (REO) equivalents for all products. [10] This was in addition to the separation and refining quota by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), which was a big challenge, because the composition of RE deposits varied a lot. This smelting and separation quotas regulates how much rare earth ore can be refined and processed into usable products. In 2010 the two sets of quotas (mining and separation) converged and, combined with the process of merging the RE firms into the six groups, the discrepancies between the quotas vanished gradually. From now on the RE groups took nearly all the mining and separation quotas.

Figure 6: The 2017 MIIT Production quota. Copyright: [7]

3.6 Illegal Mining and Environmental Policies

China originally on-shored mining capacities by not caring about the environment as much as countries with previous mining operations like the US, Australia or France. This changed in 2011 as China started using environmental concerns as a pretext to start cracking down on illegal mining and further their grip over the industry. Documents released by the state Council in 2011 and 2012 laid out a plan on how to crack down on mining, lift environmental standards and further state control:

- To change the structure of industry by controlling the capacities of mining and separation and encour- aging the innovation of new technologies in the downstream industry.

- To protect the environment and sustainability of resources by employing higher environmental stan- dards, establishing industrial order, and imposing more efficient resource and environmental taxes.

- To weed out backward production technology that are not qualified according to the emission standards, and to promote the technical transformation of the mining industry.

- To complete the laws and regulations along the supply chain for a unified, normative, and efficient RE regulation system.

- To accelerate the process of merging and creating an industrial structure led by dominant firms, including the goal that the industrial concentration of the largest three southern ionic clay RE firms should be 80%.

- To coordinate the RE industry with the local economies and the interests between different entities (central government and local government, state-owned enterprises and private firms, local government and local firms, state-owned enterprise owned by the central government and local governments).

- To coordinate the relevant national ministries and departments in terms of planning and policy imple- mentation.

Additionally the ”Environmental Protection Tax Law” was passed by the National People’s Congress of China and became effective in 2018. The law forces RE firms to internalize their environmental costs and can be used to further combat illegal production.

3.7 Mergers and Market Structure

The promotion of mergers and acquisitions started from 2002. [14] It proved to be difficult to consolidate the industry for the same reasons it is to restrict illegal mining: Local governments (especially in southern China) are reluctant to hand a key industry over to a state-owned group that is not located in their province.

A consolidation plan was officially announced in 2015 and in 2017 a MIIT document finalized the names and ownership of the groups. The central government through the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission controlled three groups. The dominant stockholders of the remaining three groups are either provincial or city governments. Each of the groups covers various parts of the RE supply chain, but all are focused on the upstream and midstream sectors. [7] Before the mergers and even to the present there are hundreds of RE firms that are run and owned by private entities that operate somewhere along the supply chain. This is the reason why, even with legal production being restricted, RE prices are low due to competition. A key development in recent years could potentially put this at risk as there is and increasing restriction on eligibility for production quotas, which went from six companies prior to 2024 to only the two state-owned groups (CREG and CNRE) in 2024. [1]

3.8 Tracing Products

In the same document outlining the environmental challenges in the industry, the MIIT started promoting the establishment of a tracing system, to help the government gain more control over the entire supply chain, but focus mainly on concentrates and separated RE products. MIIT intended to use information sharing mechanisms such as special invoices, export declarations, enterprise managerial archives, among others for RE products. [7] Recent research in the field looks at the possibility of having a digital twin following the ore trough the entire supply chain. [15]

3.9 Building domestic demand

China’s domestic consumption of RE mineral increased from 19,000 t in 2000 to 77,000 t in 2010, with an annual growth rate of 15%. [10] By 2015, Chinese domestic consumption of rare earths grew to 80% or more of domestic production. [7] Due to illegal mining, export quotas and taxes; domestic Chinese prices were significantly lower than Chinese export prices available to customers in the rest of the world. Additionally the expansion of the Chinese Economy overall lead to a an expansion in downstream manufacturing. Restrictive export polices and illegal mining (which could not at all or hardly export their products) allowed Chinese users of REs to benefit from lower prices than foreign customers. China consistently encouraged foreign investment in the RE downstream processing sector beginning in 1997. [6] In September 2016, the MIIT released the Development Plan of Rare Earth Industry with a commitment to keep carrying out policies that stimulate the development and innovation in the downstream sectors in order to increase the added value of the entire RE supply chain.[7] While the upstream sector has better financial performance as there are fewer firms due to the limitation of permits and quotas, the downstream sector (manufacturing) is more competitive.

3.9 Foreign Policy using RE

China realized the strategic value of RE products in the early 1990s when it started to regulate the industry intensively. In September 2010 a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese Coast Guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). The Senkaku Islands are a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea claimed by both countries. The Japanese Coast Guard arrested the Chinese trawler captain. This sparked a diplomatic crisis, with China demanding his immediate release. After intense pressure and an unofficial embargo of rare earth exports from Beijing, Japan eventually released the captain. [3] This lead to the already mentioned WTO Dispute and the dropping of the export quota in 2014. [13] The word ”strategic” is used for the rare earth industry In the ”2016–2020 National Mineral Resource” plan by the MLR. It also suggests the establishment of a strategic mineral detection and warning mechanism for the RE industry, creating warning indicators, threshold values, and a comprehensive evaluation model. Furthermore it suggests to establish a system of demand and supply analysis of mineral products and to intensify the ability of risk warning in the case of international conflict. In late 1989 and early 1990, Rhone-Poulenc (later Rhodia, now Solvay) was denied an extension of its radioactive waste disposal license at its RE processing plant in La Rochelle, France. As a result, this accelerated the move of its extraction and solvent-extraction facilities to China. At the same time, Japan was closing down many of its rare-earth processing facilities and transferring plant and technology to China in exchange for supply contracts. These transfers greatly assisted development of China’s upstream sector and subsequent moves downstream. Chinese upstream industry was profitable, reflecting low production costs relative to market prices and the rise of cheap illegal mining due to the absence of administrative regulations.[7]

3.10 Foreign Policy using RE

China realized the strategic value of RE products in the early 1990s when it started to regulate the industry intensively. In September 2010 a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese Coast Guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). The Senkaku Islands are a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea claimed by both countries. The Japanese Coast Guard arrested the Chinese trawler captain. This sparked a diplomatic crisis, with China demanding his immediate release. After intense pressure and an unofficial embargo of rare earth exports from Beijing, Japan eventually released the captain. [3] This lead to the already mentioned WTO Dispute and the dropping of the export quota in 2014. [13] The word ”strategic” is used for the rare earth industry In the ”2016–2020 National Mineral Resource” plan by the MLR. It also suggests the establishment of a strategic mineral detection and warning mechanism for the RE industry, creating warning indicators, threshold values, and a comprehensive evaluation model. Furthermore it suggests to establish a system of demand and supply analysis of mineral products and to intensify the ability of risk warning in the case of international conflict. In late 1989 and early 1990, Rhone-Poulenc (later Rhodia, now Solvay) was denied an extension of its radioactive waste disposal license at its RE processing plant in La Rochelle, France. As a result, this accelerated the move of its extraction and solvent-extraction facilities to China. At the same time, Japan was closing down many of its rare-earth processing facilities and transferring plant and technology to China in exchange for supply contracts. These transfers greatly assisted development of China’s upstream sector and subsequent moves downstream. Chinese upstream industry was profitable, reflecting low production costs relative to market prices and the rise of cheap illegal mining due to the absence of administrative regulations.[7]

4 Conclusion

By directing the flow of foreign investments and enabling domestic companies to learn the capabilities down the the supply chain over more then three decades, China managed to transfer not only knowledge, but also snuffed out the competition in the West. If this was a result of deliberate or accidental, caused by bad industrial policy by the West or planed by good industrial Chinese Industrial Policy remains open. A deeper look at the developments in the West and their Industrial Policy would be needed to make a decisive argument on what exactly caused the industry to move to China entirely. Future research could take a look at the following documents: “Made in China 2025,” “New Material Industry Development Plan”, “Industry Green Development Plan” and take a look at the investments by Chinese companies into the rare-earth supply chain outside of China especially in South East Asia.

References

- 2 Giants, 20 Years: The Consolidation of China’s Rare Earth Industry – Rawmaterials.Net. Feb. 2024. (Visited on 07/17/2025).

- IEA. “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025”. In: (2025).

- Japan’s Effective Control of the Senkaku Islands — Research. https://www.spf.org/islandstudies/research/a00005.html. (Visited on 07/11/2025).

- Mahmut MAT. Bastn¨asite : Properties, Uses, Occurrence ¿¿ Geology Science. Sept. 2024. (Visited on 07/14/2025).

- Elizabeth R Neustaedter et al. Compilation of Geospatial Data (GIS) for the Mineral Industries and Related Infrastructure of the People’s Republic of China. 2023. doi: 10.5066/P9HK2K8I. (Visited on 07/17/2025).

- Greta J. Orris et al. Global Rare Earth Element Occurrence Database. 2018. doi: 10.5066/F7DR2TN4. (Visited on 05/26/2025).

- Yuzhou Shen, Ruthann Moomy, and Roderick G. Eggert. “China’s Public Policies toward Rare Earths, 1975–2018”. In: Mineral Economics 33.1-2 (July 2020), pp. 127–151. issn: 2191-2203, 2191-2211. doi: 10.1007/s13563-019-00214-2. (Visited on 05/22/2025).

State-Council. Notice on Listing Tungsten, Tin, Antimony and Ionabsorbed Rare Earth as National Protective Exploitation Minerals. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-07/01/content 5087381.htm. 1991. (Visited on 06/03/2025).

State-Council. Report on Import and Export Tax and Value Added Tax. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2013- 09/06/content 2112.htm. 1985. (Visited on 06/03/2025).

- Pui-Kwan Tse. “China’s Rare-Earth Industry: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report”. In: (2011).

- USGS. Bureau of Mines Minerals Yearbook (1932-1993) — U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/natio minerals-information-center/bureau-mines-minerals-yearbook-1932-1993. (Visited on 06/03/2025).

- USGS. Rare Earths Statistics and Information — U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national- minerals-information-center/rare-earths-statistics-and-information. (Visited on 05/30/2025).

- WTO — Dispute Settlement – the Disputes – DS431. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop e/dispu e/cases e/ds431 e.ht (Visited on 07/11/2025).

- Jost Wu¨bbeke. “Rare Earth Elements in China: Policies and Narratives of Reinventing an Industry”. In: Resources Policy 38.3 (Sept. 2013), pp. 384–394. issn: 03014207. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol. 2013.05.005. (Visited on 06/02/2025).

- Hui Yang et al. “Digital Twin Key Technology on Rare Earth Process”. In: Scientific Reports 12.1 (Aug. 2022), p. 14727. issn: 2045-2322. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19090-y. (Visited on 06/03/2025).

Footnote(s)

a. A map of the entire globe and the location of mines can be found in the Appendix

Appendix

Figure 7: Active rare earth producing and as byproduct producing mines worldwide [6]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.