Date of Publication:

16 October 2025

Khai Quoc BUI

School of International Relations, Tokyo International University

Suggested Citation

(APA) Bui, Q. K. (2025). The temporality of identity and narrative in schoolgirl Yuri mangas. EAYSA Anchor. https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles-the-temporality-of-identity-and-narrative-in-schoolgirl-yuri-mangas/

(MLA) Bui, Quoc Khai. “The temporality of identity and narrative in schoolgirl Yuri mangas.” EAYSA Anchor, 2025, https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles-the-temporality-of-identity-and-narrative-in-schoolgirl-yuri-mangas/

(Harvard) Bui, Q.K., 2025. The temporality of identity and narrative in schoolgirl Yuri mangas. EAYSA Anchor. Available at: https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles-the-temporality-of-identity-and-narrative-in-schoolgirl-yuri-mangas/

Editorial Note(s)

This work was accepted to and presented at the 2025 Youth Symposium: The Intersection of Research, Civil Society, and Young People in East Asia, held at the University of Tokyo, from 22 to 24 August 2025.

Abstract

Recently, there has been a surge in depictions of female same-sex romance in Japanese popular entertainment, which remains relatively understudied. This paper seeks to contribute to the English-language academic literature on this trend through analysing the temporal structure of various schoolgirl yuri mangas, arguably the most important template in the genre. To do so, the paper adopts a narratological approach inspired by Koselleck’s theory of history to examine two key aspects of schoolgirl yuri manga stories: the protagonists’ sexuality and the narrative course of their relationships. This paper argues that mainstream schoolgirl yuri mangas have constructed their protagonist’s sexual identity as ‘temporary’ lesbians, meaning that they are attracted to only one woman for a limited time. Furthermore, the course of their romantic relationships is invariably cyclical, neither progressing towards definite confessions nor ending in breakup until the very end of the story. However, such constructions have been challenged by yuri mangas outside the mainstream, which have mounted powerful critiques of this cyclical temporal paradigm either through taking its premises to extreme conclusions or through constructing entirely new temporal paradigm featuring definite progress.

Keywords: Yuri, Temporality, Sexual Identity, Lesbianism, Shoujo

Introduction

Recently, there has been a surge in depictions of female same-sex romance throughout the Japanese popular entertainment industry, evidenced by such high-profile yuri anime adaptations as I Admire Magical Girls, and… (2024/1); Ninja and Assassin Living Together (2025/4); and This Monster Wants to Eat Me (2025/10). This essay is intended to contribute to academic understanding of this trend through outlining the temporal structure of the schoolgirl yuri story, arguably the most influential narrative template in the genre. Its central thesis runs thus: The schoolgirl yuri subgenre (and its main source of influence shoujo literature) is homoerotic insofar as their narratives occur and recur in a space and time enclosed from wider society. However, this self-quarantine has not gone unchallenged from within the subgenre.

The paper is organized as follows: first, there will be a brief description on the historical development of yuri as a genre as well as the methodology employed to analyze yuri manga series in this paper; second, the analysis will focus on mainstream schoolgirl yuri mangas in order to demonstrate their temporal insularity; third, the discussion will turn to less mainstream schoolgirl yuri mangas to explore how they challenge the dominant temporal paradigm; finally, the paper will close with some remarks on recent developments in the yuri genre which are of potential academic interests.

Background

Female same-sex love has been a recurring theme in Japanese popular culture since the late Meiji era. According to Dollase (2019, p. 38), one of its most prominent early depictions is Yoshiya Nobuko’s Flower Tales (1924), a collection of shoujo (aimed at young women) short stories revolving around the daily lives of and friendship, occasionally crossing into love, between schoolgirls. She also notes that most of these relationships, known as S-kankei (S means Sister), happen in secluded places, removed from the rest of Japanese society, a recurring motif as we will see later. Such S-kankei was not limited to the literary imagination but was in fact a widespread social trend in girl’s schools throughout Japan, surviving the war well into the 1950s and 60s (Pflugfelder, 2005, p. 174).

In the manga world, such same-sex love was first treated as a subject by a few shoujo manga series in the 1970s, but it was not until the turn of the century that yuri fully emerged as a distinct genre (Fanasca, 2020, p. 52). Nonetheless, the genre continues to draw inspiration from the shoujo cultural sphere to the present day, with this influence clearest in the schoolgirl yuri manga published throughout the past 20 years. Despite this long history, yuri has attracted comparatively less academic attention than its male homosexual counterpart, yaoi. In fact, English-language analyses of the genre were thus far largely confined to a handful of older works such as Sailor Moon (Baily, 2012; Burgos, 2021; Yatron, 2022), Revolutionary Girl Utena (Baily, 2012; Cornejo, 2021),and Puella Magi Madoka Magica (Cooley, 2020). This paper thus fills a crucial gap in Western literature through discussing previously overlooked mangas.

Methodology

Starting from Fisher’s (1989) contention that all forms of human communication are implicitly political insofar as they propose certain ways to organize our lives and our relationships with one another (p. 63), this essay seeks to uncover the political messaging of contemporary schoolgirl and non-schoolgirl yuri manga series through examining two key characteristics of the spatio-temporal structural characteristics of these series. For more information on the manga series examined in this article, please refer to the Appendix.

First, there is the distinction between a universalizing and minoritizing view of female same-sex attraction. As described by Makoto (1994, p. 114), this view, drawn from 20th-century sexological theories, recognizes two types of female homosexuality (douseiai): a transitory phase during young adulthood and a congenital condition of deviant sexuality. The former was treated as inherently ‘temporary’ in nature, an emotional bond which only rarely crosses into love (Sedgwick, 1990, p. 44). Indeed, some commentators even argued for the crucial role of these relationships in preparing women for permanent heterosexuality later in life (Pflugfelder, 2005, p. 140). Accordingly, failure to outgrow this transitory phase is seen as a sign of mental illness requiring psychological therapy. Inheriting this baggage, yuri stories rarely depict schoolgirls as ‘permanent’ lesbians, who can in theory be attracted to multiple women, and instead idolize the monogamous connection between two close friends. It should be noted here that until very recently, almost no yuri stories outside of pornographic content depicted contemporaneous polygamy – attraction to multiple women at the same time. As a result, the analysis here will mainly focus on the distinction between monogamy and serial polygamy – attraction to one woman after loss of attraction to another, as a proximate marker for ‘temporary’ and ‘permanent’ lesbianism.

Secondly, the narrative structure of these series, specifically the sequencing of romantic developments between the protagonists, will be analyzed to distinguish between what Koselleck has termed cyclical and progressive temporality. In the collection of essays Futures Past (2004), he argued that the shift to modernity is marked by a change in conception of time in Europe. More precisely, mediaeval historians conceived of the present as an endless repetition of the past and the future as delimited by the Christian Doomsday, while modern ones, shorn of eschatological expectations, are free to imagine the passage of time as limitless progress from an ignorant past to an enlightened future (p. 232). This fundamental shift in perspective, he contended, is responsible for the rise of political ideologies and grand narratives from the 18th century onwards (p. 266). A comparable pattern can be observed in yuri mangas: insofar as a yuri story adopts a cyclical framework, it is unable to introduce radically new developments into the existing relationship (such as a new love interest) and thus cannot imagine a future outside of the existing present.

Dominant Temporal Paradigm

In this section, to illustrate the typical temporal structure of the schoolgirl yuri subgenre, the paper will examine two series: Sasameki Koto (Whispered Words, henceforth Sasakoto), and Watashi o Tabetai, Hitodenashi (This Monster wants to Eat me, henceforth Watatabe). Sasakoto, serialized between 2007-2013, was among the first yuri mangas to explicitly foreground the romantic nature of the relationship between its protagonists, Kazama and Murasame. Murasame, a tomboyish high school student, was romantically interested in her classmate Kazama but believed that her love would not be reciprocated as Kazama appeared exclusively attracted to feminine-presenting women (Vol. 1, Ch. 1). However, Kazama’s crushes were based solely on physical attraction and inevitably ended in rejection (Vol. 3, Ch. 14). After the first few volumes, this potential for other relationships is permanently closed off as Kazama realized her sole love was for Murasame. The narrative thus erects a dichotomy between ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ lesbianism, positing ironically that only the latter can produce a long-lasting and emotionally fulfilling relationship.

The framing in Watatabe is seemingly the opposite: both protagonists appear asexual at first glance. Hinako was traumatized by her family’s tragic death in an automobile accident and suffered from recurring bouts of depressive and suicidal thoughts. She was thus drawn to Shiori, the titular ‘monster’, who vowed to consume her if she could overcome her trauma (Vol. 1, Ch. 1). Afterwards, Shiori took on human form and joined Hinako’s class to stop her from committing suicide by other means. Thus, by ways of a magical bond, the narrative precludes the possibility of romance between the two protagonists and other female characters. Such monogamous relationships are reminiscent of earlier shoujo short stories and reveal a fundamentally sexological worldview. In adopting this framework, these modern yuri series have failed to adequately address the ‘permanent’ lesbian sexual identity.

Second, each of the above series, despite their different plot organizations, fundamentally share the same cyclical sequence of romantic development (see Fig. 1). At the beginning, there is a misunderstanding between the two protagonists. As this misunderstanding deepened, the distance between the protagonists grew until the climax, where decisive action from one (or both) party resolved the misunderstanding. There is then a short period of reflection before a new misunderstanding arises, beginning the cycle anew. For example, in Watatabe, during a school trip, Shiori told Hinako that her decision to pursue a relationship with the latter was entirely self-interested (Vol. 4, Ch. 16). This rejection caused Hinako to spiral into depression, which culminates in her acquiescence to another monster attempting to murder her. However, Shiori intervened just in time to save Hinako, in the process revealing her true form as a monster herself (Vol. 4, Ch. 18). After this resolution, Shiori’s continued failure to express her true feelings to Hinako continued to cause further misunderstandings.

Figure 1: The narrative cycle of romance in yuri stories

A similar cycle can be observed in Sasakoto, in its most condensed form lasting a single chapter (Vol. 1, Ch. 1). Kazama experienced a crush on an upperclasswoman working in the same library but was physically abused by the latter because her own crush had expressed affection towards Kazama earlier. In the end, she found consolation in Murasame, who was torn between happiness at her trust and pain at her lack of romantic affection. In the next chapter, Kazama experienced a new crush, a magazine model, and promptly began to stalk her, restarting the cycle. Such cyclical romantic development serves to close off the protagonists’ space of experience from the normal flow of time. Not unlike medieval chronology which constantly delays the Last Judgement through denying the existence of radically new events (Koselleck, 2004, p. 13), repetition of plot beats in yuri narratives delays the eventual entry of their protagonists into heteronormative society and its attendant challenges to maintaining a lesbian relationship.

Nonetheless, despite such attempts at delay, these series cannot be extended indefinitely. As Watatabe is still ongoing, the analysis will focus mainly on Sasakoto, which officially ended in 2013. After their high school graduation ceremony, Kazama finally confessed to Murasame in their classroom, and they kissed each other. At this juncture, other side characters, who had prepared the classroom for the couple beforehand, can be seen hiding outside, where the gaze of the reader is also positioned (Vol. 9; Ch. 52). The reader was thus permitted entry into the narrative, but only as a passive observer who can indirectly influence but must not intrude into the world of the protagonists. As a result, to the very end, Sasakoto seeks to cordon off the space where same-sex relationships can happen, permitting little more than the voyeuristic gaze to pass beyond the line. In other words, the endings (or lack thereof) of yuri narratives play a crucial ideological role in maintaining the separation between the in-narrative and out-of-narrative worlds. Such a self-consciously dichotomous division stands in stark contrast to yaoi mangas, which often blurred the boundary between story and reality (Nagaike, 2003, p. 85) and can even inspire real-life political movements (Chang & Tian, 2021).

Alternative Temporal Paradigms

Cyclical temporality as described above is dominant but far from the sole paradigm in the subgenre. In this section, the paper will examine two alternative temporal structures: the backward glance in Yume no Hashibashi (The Ends of a Dream, henceforth Yumebashi), and progressive temporality (Koselleck, 2004, p. 36) in Haru tsudzuru, Sakura saku, Kono Heya de (Composing Spring in this Room where Cherry Blossoms Bloom, henceforth Harusaku). In the former story, the protagonists Mitsu and Kiyoko’s memory of lost schoolgirl love was symbolized by a diary (Vol. 1, Ch. 1). After Mitsu died of old age in the first chapter, the rest of the narrative was organized counter-chronologically as a series of missed romantic moments between the two protagonists stretching from the present day back into the immediate post-war years, when they failed to commit suicide together in high school (Vol. 2, Ch. 6-9). In the final chapter (Vol. 2, Ch. 10), the narrative returns to the present day with an elderly Kiyoko leaving her house in search of Mitsu, eventually passing away to be reunited in death with her lover.

On its face, this narrative borrows many elements from the earliest shoujo era: in Pear Flower, the last story in Yoshiya’s Flower Tale, two schoolgirls committed suicide to prevent their own entry into adulthood (Dollase, 2019, p. 40). Yumebashi‘s deferral of the protagonists’ unnatural deaths until they virtually coincided with natural ones, however, highlights the impossibility of escape from patriarchal society. Indeed, their families repeatedly conspired either to separate the two young women (Vol. 2, Ch. 7), or to force Kiyoko into a loveless marriage (Vol. 1, Ch. 5). However, it is implied that the true reason for Kiyoko and Mitsu’s inability to maintain a romantic relationship into adulthood is not patriarchal intrusion but rather their incompatible personalities, which caused them to repeatedly drift apart after each reunion (Vol. 1, Ch. 3). That they were unable to move on and find other romantic interests, even in death, can thus be understood as Yumebashi‘s critique of the ideals of monogamous lesbian love and its concomitant failure to imagine a future for any one of its protagonists without the other.

In contrast, Harusaku employs a progressive temporal paradigm which recenters the lesbian as a member of society, possessed of a past, present, and future. Starting several years after the sudden death of one of its protagonists, Sakura, the narrative follows Haruki, the surviving protagonist, as she learns to move on. The figure of the ‘permanent’ lesbian, who can love more than one woman, is thus the focus from the start. Furthermore, although the memory of lost love was similarly symbolized by a diary from Sakura, its approach to the past was radically different from Yumebashi. Instead of merely reading the diary to vicariously re-live past moments of intimacy, in Harusaku Haruki sets out to complete it by reconnecting with the two protagonists’ mutual acquaintances and making new memories (Vol. 1., Ch. 4-6; Vol. 2, Ch. 8-12), culminating with her finding motivation to continue living independent of Sakura (Vol. 2, Ch. 14).

In place of a cycle of misunderstandings, there is only one which occupies a central position in Harusaku’s narrative: for much of the story, Haruki mistakenly believed her hallucinations as Sakura truly returning from the dead (Vol. 1, Ch. 1; Vol. 2, Ch. 12). The resolution of this misunderstanding (Vol. 2, Ch. 13) is a crucial step towards resolving the central plot point, encapsulating the series’ progressive paradigm of radical transformation over repetition with slight differences. In short, Harusaku shows not only the possibility of lesbian love in adult life but also the possibility of continued lesbian existence even in the absence of love. The story thus sustains a form of resistance against patriarchal society distinct from shoujo literature and schoolgirl yuri mangas, replacing their prior message of ‘We died/failed because of…’ with ‘We will live regardless.’

Conclusion

This essay has examined one significant subgenre of yuri manga, the schoolgirl story, in order to sketch out its conventions as well as its ideological underpinnings. Through the presentation of the protagonists’ sexuality and the cyclical master narrative governing their romance, the mainstream schoolgirl slice-of-life yuri subgenre has constructed a hermetically sealed space and time and thus insulated its protagonists and their relationships from greater society. In contrast, more niche schoolgirl yuri mangas have been bolder in their protest of heteronormative norms by explicitly showing society’s intrusion into lesbian romance. It must be emphasized here that this essay does not praise or condemn either approach to storytelling as both create narrative spaces where one can safely engage with queerdom.

This study has so far examined only a part of the yuri genre; however, as noted in the beginning, the yuri genre has become more mainstream in recent years, leading to a greater variety of relationships depicted. Most notable among these new developments are ‘toxic’ yuri, ‘villainess’ yuri, and ‘brothel’ yuri. First, ‘toxic’ yuri refers to stories centered around dysfunctional or abusive relationship dynamics. Emerging with Manio’s I Love your Cruddy in 2019, the subgenre has recently seen an impressive growth in popularity with such stories as My Girlfriend’s not here Today (2021-ongoing) and Destroy Everything and Love me in Hell (2023-ongoing). Usually set in high school or college, these stories can be seen as a dark mirror to the more wholesome tone of schoolgirl yuri stories examined earlier due to their dramatization of a wide range of taboo acts from codependency to emotional and physical abuse or even rape and murder. Nonetheless, the separation is not dichotomous as some stories combine elements from both subgenres, most prominently Watatabe as examined above.

Second, ‘villainess’ yuri is a subgenre focused on relationships between the heroine and villainess of a fantasy setting. Examples of the genre include I Favor the Villainess (2020-ongoing) and The Fed-up Office Lady Wants to Serve the Villainess (2022-ongoing). Many series seek to subvert otome media (aimed at young women): the main character is transported from our world to the mediaeval or early modern fantasy setting of her favorite otome media; however, she chooses to romance the female ‘villainess’ of the setting rather than her designated love interests, the male ‘heroes’. Her efforts are nonetheless frequently frustrated by the meta-narrative of conflict between the protagonist-as- ‘heroine’ and the ‘villainess’, thus leading to the familiar cycle of romantic development discussed above. Finally, the ‘brothel’ yuri subgenre, named after Asumi-chan is Interested in Lesbian Brothels! (2021-ongoing), often features protagonists engaging the services of multiple female sex workers. These encounters are usually of a transactional and temporary nature, thus emphasizing the protagonist’s physiological needs over yuri’s usual focus on romantic-emotional ones. Together, these new subgenres represent a greater diversity of influences on the genre outside of its shoujo roots. More in-depth studies of these emerging subgenres would thus substantially improve academic understanding of the yuri genre.

Outside the narrative content of yuri stories themselves, there have also been significant developments in the production and consumption of these stories, most notably the trend of transmedialization. Whereas yuri content was largely restricted to a single medium (usually manga) in the past, now many yuri stories, for example Watatabe and I Admire Magical Girls, and…, are veritably transmedia enterprises, encompassing light novels, mangas, audio dramas, animes, game collaborations, ASMR podcasts, physical merchandises, and more. Such growing prominence of transmedial productions is consistent with Steinberg’s (2012) analysis of anime media-mix strategy: yuri is simultaneously adapted into more capital-intensive brand-building mediums (animes) and less capital-intensive brand-exploiting mediums (toys and other licensed commodities) to maximize profits (pp. 39-40). In the process, however, the progressive messaging within the original stories is often distorted, for example Studio Ghibli’s environmentalist animes providing the basis for mass-produced plastic figurines and lifestyle goods (Tvorun-Dunn & Pascaru, 2023, pp. 897-898). Similarly, yuri stories and its male homoerotic counterpart, yaoi, also risk losing their subversive critique of heteronormativity due to entanglement with market forces. Therefore, studying the specificities of yuri media-mix in contrast with other queer and non-queer intellectual properties can help outline the contemporary landscape of Japanese popular culture as a whole and its future trajectory.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Barbara Greene for her helpful advice and support throughout my research project, to Helix Lo, my managing editor, for his continuous guidance during this article’s revision process, and to Teguh Ganesha and Evan Ronny Hotasi, my colleagues, for their many constructive comments. I also would like to thank the East Asia Young Scholars’ Association for granting me this opportunity to publish my work.

Author Note

All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Bui Quoc Khai. Email: quockhai082004@gmail.com

References

Primary sources

Aonoshita. (2020-present). 私の推しは悪役令嬢。(I Favor the Villainess). Ichijinsha. Original light novel by Inori.

Hamburger. (2021-present). 忍者と殺し屋のふたりぐらし (Ninja and Assassin Living Together). Kadokawa.

Ikeda Takashi. (2007-2013). ささめきこと (Whispered Words). Ichijinsha.

Itsuki Kuro. (2021-present). 彩純ちゃんはレズ風俗に興味があります! (Asumi-chan is Interested in Lesbian Brothels!). Ichijinsha.

Iwami Kiyoko. (2021-present). 今日はカノジョがいないから (My Girlfriend’s not here Today). Ichijinsha.

Kuwabara Tamotsu. (2023-present). ぜんぶ壊して地獄で愛して (Destroy Everything and Love me in Hell). Ichijinsha.

Manio. (2019-2022). きたない君がいちばんかわいい (I Love your Cruddy). Ichijinsha.

Naekawa Sai. (2020-present). 私を喰べたい、ひとでなし (This Monster Wants to Eat Me). Kadokawa.

Nekotarou. (2022-present). 限界OLさんは悪役令嬢さまに仕えたい (The Fed-up Office Lady Wants to Serve the Villainess). Akita Shoten.

Ononaka Akihiro. (2019-present). 魔法少女にあこがれて (I Admire Magical Girls, and…). Takeshobo.

Sudou Yumi. (2018-2020). 夢の端々 (The Ends of a Dream). Shodensha.

Tokuwotsumu. (2021-2022). 春綴る、桜咲く、この部屋で (Composing Spring in this Room Where Cherry Blossoms Bloom). Square Enix.

Secondary sources

Baily, C. E. (2012). Prince Charming by day, Superheroine by night? Subversive sexualities and gender fluidity in Revolutionary Girl Utena and Sailor Moon. Colloquy, 24, 207-222. https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1772622/bailey.pdf

Burgos, D. (2021). The queer glow up of Hero-Sword legacies in She-Ra, Korra, and Sailor Moon. Open Cultural Studies, 5(1), 248-261. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2020-0135

Chang, J., & Tian, H. (2021). Girl power in boy love: Yaoi, online female counterculture, and digital feminism in China. Feminist Media Studies, 21(4), 604–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1803942

Cooley. (2020). A cycle, not a phase: Love between magical girls amidst the trauma of Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Mechademia: Second Arc, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.5749/mech.13.1.0024

Cornejo, G. (2021). The Sedgwickian queerness of an anime lesbian: Reading Revolutionary Girl Utena. Lectora: Revista de Dones i Textualitat, 27, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1344/Lectora2021.27.10

Dollase, H. T. (2019). Age of Shōjo : The Emergence, Evolution, and Power of Japanese Girls’ Magazine Fiction. State University of New York Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781438473925

Fanasca, M. (2020). Tales of lilies and girls’ love: The depiction of female/female relationships in yuri manga. In D. Cucinelli & A. Scibetta (Eds.), Tracing pathways 雲路: Interdisciplinary studies on modern and contemporary East Asia (1st ed., Vol. 220, pp. 51-66). Firenze University Press. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-5518-260-7

Fisher, W. R. (1989). Human communication as narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. University of South Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nwbqtk

Koselleck, R. (2004). Futures past: On the semantics of historical time (trans. K. Tribe). Columbia University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/kose12770

Makoto, F., (1994). The Changing Nature of Sexuality: The Three Codes Framing Homosexuality in Modern Japan (A. Lockyer trans.). U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal English Supplement, 7, 98–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42772078

Nagaike, K. (2003). Perverse sexualities, perversive desires: Representations of female fantasies and “Yaoi Manga” as pornography directed at women. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, 25, 76–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42771904

Pflugfelder, G. M. (2005). “S” is for Sister: Schoolgirl intimacy and “Same-Sex Love” in early twentieth-century ]apan. In B. Molony & K. Uno (Eds.), Gendering Modern Japanese History (pp. 133-190). Harvard University Press.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). Epistemology of the closet. University of California Press.

Steinberg, M. (2012). Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttscmj

Tvorun-Dunn, M., & Pascaru, N. (2023). Environmentalism polluted: Consumerism and complicity in Studio Ghibli’s media mix. Journal of Cultural Economy, 16(6), 886–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2023.2225548

Yatron, C. (2022). 30 years later, re-examining the “pretty soldier”: A gender study analysis of Sailor Moon. The Journal of Anime and Manga Studies, 3, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.jams.v3.948

Appendix

Publication Information for Analyzed Mangas

Table 1: Manga Information

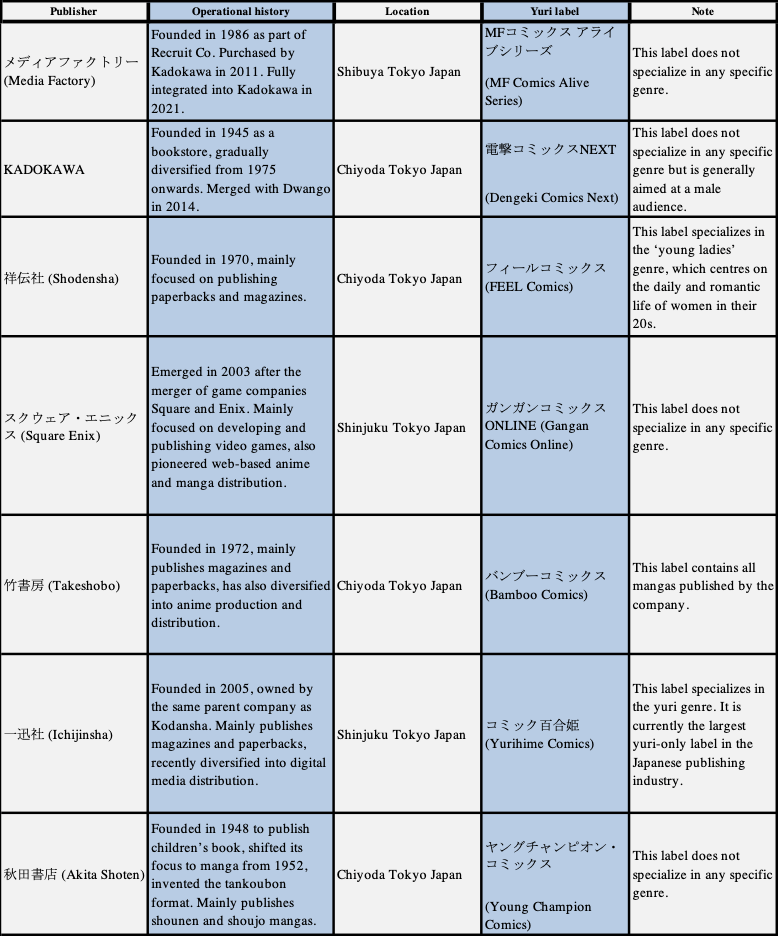

Table 2: Publisher Information

Most Japanese publishers tend to group works in specific genres under subsidiary labels (レーベル) for publishing. Table 2 will provide a brief history for the publishers included in Table 1, alongside the labels under which they usually publish yuri mangas.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Share this article