Date of Publication:

4 November 2025 (Appendices revised on 8 Novemember 2025)

Sophia Isaacson

American University and Ritsumeikan University, “Sakura Scholar” Alum, isaacsonsophia@gmail.com

Logan Day

American University and Ritsumeikan University, “Sakura Scholar” Alum, logandaytwo@gmail.com

Suggested Citation

(APA) Isaacson, S. & Day, L. (2025). DM For Details:How Young LGBT Activist Groups use X to Create Community. EAYSA Anchor. https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles/dm-for-detailshow-young-lgbt-activist-groups-use-x-to-create-community/

(MLA) Isaacson, Sophia & Logan Day. “DM For Details:How Young LGBT Activist Groups use X to Create Community.” EAYSA Anchor, 2025, https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles/dm-for-detailshow-young-lgbt-activist-groups-use-x-to-create-community/

(Harvard) Isaacson, S. & Day, L. 2025. DM For Details:How Young LGBT Activist Groups use X to Create Community. EAYSA Anchor. Available at: https://eaysa.org/anchor-articles/dm-for-detailshow-young-lgbt-activist-groups-use-x-to-create-community/

Editorial Note(s)

This work was accepted to and presented at the 2025 Youth Symposium: The Intersection of Research, Civil Society, and Young People in East Asia, held at the University of Tokyo, from 22 to 24 August 2025.

Abstract

The authors focus on young Japanese LGBT activists to highlight the new, digital kinds of tools used and strategies pursued to create change. Through a survey and selective sampling of X posts by six queer Kansai-based activist groups, the authors examined habits based on six critical factors: youth, queer (LGBT), activism, information sharing, praxis, and Kansai. While preliminary, the results suggest a deeply interconnected and evolving online ecosystem. Contrary to expectations, the groups studied shied away from strategies that would maximize views, preferring to create boundaries around interaction. Moreover, groups utilized X as a pathway to alternative platforms and participation, not as an end stop resource. Community events and education were the biggest focus for groups, suggesting a shift towards hyperlocal activism over grand coalition-building. In sum, young LGBT activists are certainly present and aware of legal developments, but the goal of creating safe community spaces and region communities is the priority.

Keywords: Japan, Youth, LGBT, Activism, information-sharing, Kansai

Introduction

Since the 2000s, movements like the “Marriage for All” campaign, have built a patchwork of protections for Japanese LGBT people through local partnership ordinances and regional court cases.[1] But studies show that queer people still remain more talked about than talked to,[2] especially regarding recent Liberal Democratic Party discrimination scandals.[3] In effect, current landscapes for queer people in Japan sit in a liminal space between monumental success and gross misrepresentation—emblematic in recent legislation, like the 2023 LGBT Understanding Promotion Bill.[4] So how is the next generation of rising queer leaders tackling this challenge? With Japanese media awash with references to youth political apathy[5] or Japan’s declining birthrate,[6] answers are unclear. But we hypothesize that youth are organizing, just in new places.

Like any other country,[7] Japan’s new generations are increasingly organizing on Social Networking Sites (SNS), like Instagram, X, TikTok, and YouTube. The 2015 SEALDs movement[8] and the 2018 “LGBT Stonewall”[9] protests revealed this, showing the catalytic role of SNS sites for young and LGBT activists. Especially during COVID-19,[10] people witnessed digital platforms expanding sociopolitical and communal conversations. Now, we know that 99.5% of young Japanese people (20-29 years old) flock to digital spaces for connection.[11] Yet little research has highlighted digital communication as a robust avenue to answer fundamental questions about contemporary movements. As we pass the halfway mark of the 2020s, it is time to catch up on recent evolutions of queer activism in Japan. We must ask, what is the landscape of activism for contemporary young queer Japanese activists trending towards as online communication evolves?

Methodology

This study evaluated the hypothesis through an ethnographic regional case study of groups from Japan’s Kansai region on X, spanning from January 2022 to January 2025. Researchers attempted to gather data, from 18 months before and after the passage of the 2023 LGBT Understanding Promotion Bill, to capture reactions to and debate of the bill, as well as monitor for any shifts afterwards. Researchers focused on Kansai, as the secondary “core” for Japan’s LGBT populace outside of Tokyo, to evaluate behaviors within an integral—but often overlooked—region. Finally, researchers chose X becauseof its popularity and prominence within activist spaces. Overall, the case study was structured within an analytical conceptual framework. This allowed the framework for the case to be anchored around thematic concepts common to topical academia. It also helped streamline relevant data collection and build a foundation for comparative analysis. The six analytical concepts chosen are as defined:

- “Youth,” or ‘young’: indicates people aged eighteen to twenty-nine, relatively all a general college-going age. This range combines the age spectrum found within data on young persons in Japan from MIC datasets[12] and studies on young, queer Japanese persons in general (often in university);[13]

- “LGBT”: LGBT is the most common-use term within Japanese social and political spaces[14] and is treated as equivalent to queer or LGBTQ+;

- “Activism”: based on scholarship in Japan’s context,[15] includes small feats, community building, and regional momentum that, foremost, breaks homogenous assumptions and expands policy to include LGBT members;

- “Information sharing” (IS): Refers to communication methods mentioned, such as DMing versus TV broadcasting. IS focuses on communicators as a “conduit”[16] and what patterns emerge in their sharing, i.e., communication formed through formal debate or casual conversation;

- “Praxis”: Refers to the practices and tactics that enable IS. Praxis underscores the medium through which IS occurs. For example, a blog versus brochure or Zoom versus Instagram;

- “Kansai”: Refers to the western area of Japan’s main island, interpreted here as its major metropolitan areas surrounding Osaka, Kobe, Kyoto, and Nara. This interpretation coincides with trends of hierarchy[17] for LGBT communities in Western Japan.[18]

With parameters set, researchers began subject selection and data collection in full. Using convenience sampling, researchers identified six Kansai-region LGBT advocacy groups through search engines and referrals. Aside from having varied levels of youth engagement and being based within Kansai, these groups were also chosen because of their clear activity both on X (from January 2022 to January 2025) and other platforms/offline. Of the six chosen, three groups (‘A,’ ‘E,’ and ‘F’) are university-based (for-youth, by-youth) and three groups (‘B,’ ‘C,’ and ‘D’) are independent organizations (target youth, but not only for- or by-youth). After selection, researchers contacted all groups via DM, website forms, and email to ask for their voluntary participation in a 10-minute survey. The survey (Appendix A) results serve as additional primary source context for observations.

Following initial outreach and while awaiting responses, researchers collected applicable, publicly available, and free-to-access X content posted by the groups. All posts were compiled into a tailored Excel database organized by group, with individual posts arranged chronologically by row. Columns recorded each entry’s timestamp, post type (original tweet or repost), content function (sharing information, building community, or sourcing interaction), English translation, and presence or absence of each analytical concept within post text. To avoid ‘spam’ content, duplicate or copy-and-paste (re)posts were excluded from all group datasets.

After collection, researchers applied thematic coding to posts, sorting keywords and rhetorical patterns according to the six concepts. Researchers chose this additional step to be able to contextualize into how language and framing within posts aligned with collected data. The cumulative results of data collection, thematic rhetorical coding, and the voluntary survey created swaths of comprehensive quantitative and qualitative data to help observe online communication strategies, how they are used, and how they evolve with activist efforts.

Analysis

To note, this study is an exploratory account aimed at prompting further study. To foster full transparency, all researchers’ data is available upon request. For this essay and for brevity, one primary observation per concept is presented. Further observations will appear in the full report.

Voluntary Survey Results

One of the largest endeavors of our first phase of research was survey recruitment. Despite several attempts to make contact, only one of the six groups (‘Group A’) filled out the survey. With one response, it is difficult to formulate detailed observations. However, instead of excluding the data, researchers opted to utilize the content to reinforce arguments that have academic and data support. Below are the main findings gathered from their responses.

Group A (university-based) gave an overview of their club. They said that they allow any queer person on campus to join, and that a majority (60-80%) of their members were between 18-29-years-old. They hold meetings in classrooms and communicate mainly through an email address and their website. For the future, they hope to use X to reach more people. Notably, Group A ranked the following communication methods from most important to least important: events, SNS, zines, blogs, and posters. As requested, the group provided two examples of events. The first concerned queer history education, and the second was a Pride awareness campaign. Importantly, they said neither represented Group A’s usual types of events.

These results were largely unanticipated, as there was an emphasis on in-person events and a deemphasis on social media. We found a large body of prior posts under their account name on X, which suggests a potential disconnect between Group A’s past and present leadership.

Data and Coding Results

“Youth”

In contrast to expectations, “youth” as an analytical term was the least mentioned concept. One explanation for the low mention of anticipated “youth” keywords is that at least half of selected groups operate with a default assumption that their primary audience is young people. For example, Group A offers exclusive membership to their on-campus queer community, as seen in this post:[19]

“We are recruiting members for our club! The target is students of University A who are part of the LGBTs community. We also warmly welcome those who are unsure about their own sexuality. To those interested in our club! We regularly hold lunch gatherings and discussions!”

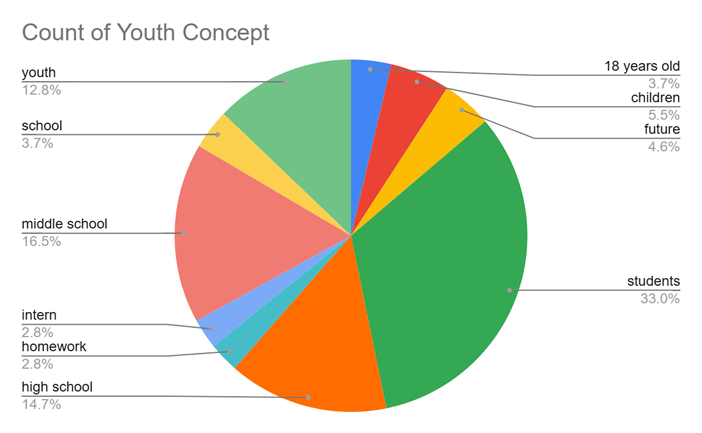

Feel free to reach out via DM or email, we’re looking forward to hearing from you! For Group A, collegiate attendance (being a student) substitutes for age, and negates Group A’s need to advertise such requirements. All the university-based groups displayed similar trends in rhetoric, suggesting that explicit “young” age is not a defining characteristic. In contrast, non-university-based groups lack this context. To combat feelings of exclusion, their invitations are explicit. Holistically, the habits of all groups might explain why 33% of “youth” concept content mentioned “students,” with non-university groups needing to be clear leading to an additional 16.5% mentions of “middle school” and 14.7% mentions of “high school.” Under-aged students are likely an overlooked group who would require explicit welcome to feel included. Thus, “student” becomes more relevant than age, and youth as a concept could include multiple generations. Although “youth” should emphasize mobilizable demographics (university-aged, with suffrage), it’s clear that defining the term with voting eligibility-based labels is overlooking the reality of this category online.

“LGBT”

As expected, Western labels, like “LGBT,” were extraordinarily common. Variations of the English-derived “LGBT” comprised a cumulative 44% of this concept’s mentions. The prominence of western labels matches current academic reflections on the goals of communication and online globalization/platform imperialism,[20] as seen in the hashtags and post advertisements where English-loan words are used to draw attention. Unexpectedly, these labels sometimes coexisted with synonymous native Japanese labels. For instance, Group D’s fundraising posts used English hashtags like “crowdfunding,” “LGBTQ,” and “diversity.” But, in one case, they paired “diversity” in katakana (“#ダイバーシティ”) and kanji (“#多様性”). From a campaign perspective, Group D may have done this to maximize a diverse audience’s understanding of terms and to align their brand with Western messaging.

At the same time, it was clear that some groups were using this chance to re-localize terminology. Most notable was with the term “rainbow,” which comprised 13.1% of “LGBT” concept mentions and appeared as both katakana and native Japanese. The term “rainbow” alludes to the rainbow flag and in Japanese could be used as an all-encompassing umbrella term. The use of a native term among Western loanwords could suggest an evolution of dialogue shifting away from globalized defaults along with a new way to reference a unique Japanese queer experience.

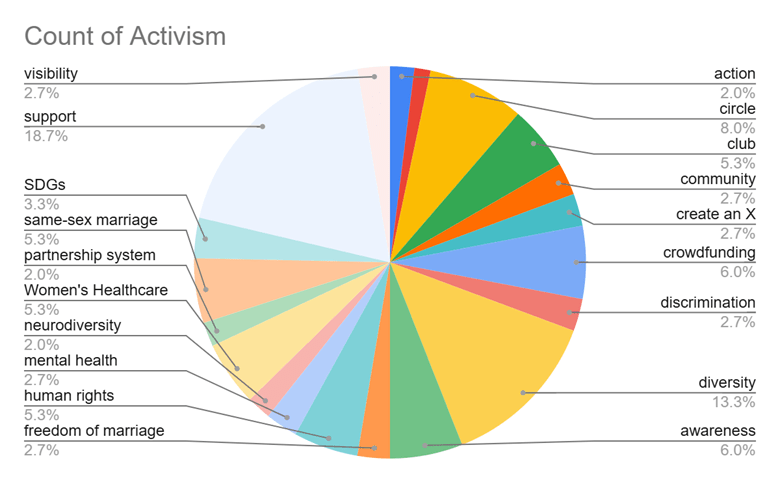

“Activism”

Most data collected under the concept of “activism” centered on community building and awareness. In fact, of the rhetoric pertaining to the ‘activism’ concept, the largest percentage related to a specific political issue was marriage equality at 10%. Comparatively, 18.7% pertained to social support initiatives and 13.3% to building a diverse society. For example, on December 25, 2023, Group F posted:

“Merry Christmas everyone #GroupFGF We are publishing articles from the Human Rights Week wall newspaper at the beginning of this month! This week’s article is about how LGBT is actually …… Please read it! [blog post link] #GroupFUniversity #GFU #LGBTQ #GF #HumanRightsWeek”

As seen, there is no identifiable goal, leader, or political party emphasized. Instead, Group F asks people to come together and learn, a common theme among “activism” concept inclusive posts. Overall, a clear observation of Group F’s and other groups’ posts around “activism” was that the term sat in a hybridized space where calls for justice were made, but few major calls to action on the local scene were explicit. Sometimes posts contribute to the national debate around marriage or discrimination, but they were outnumbered by posts dedicated to providing community services.

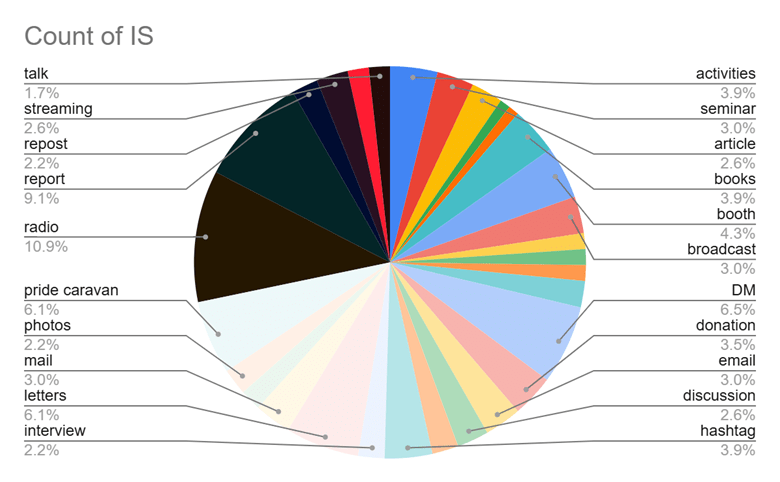

“IS”

X lends itself to particular posting styles—often including images and short texts—but the style and content within those limitations varied widely among groups. Specifically, some preferred to share friendly radio shows (podcasts; 10.9% of mentions) versus others who published formal reports (9.1%). Sending personal Direct Messages (DMs; 6.5%) as a way to reach people, however, was a common trend for everyone. As shown in Group E’s April 2024 post:

“Congratulations to everyone who has been accepted to E University🌸 Group E is a club open only to sexual minority people who are students at University E🙌! We hold dinner parties, movie nights, and other events on an irregular basis! Please feel free to contact us by DM or email if you are interested 🙏#UniversityEfromSpring #LGBTQ”

This post only hints at social events and requires extra steps to actually attend. To note, this “gatekeeper” style of posting is not done out of malice. In fact, like this post, all moderators took careful steps to signal friendly openness, no matter what group. They employ emojis and welcoming language to inject a casual, fun tone into an otherwise dry request. Researchers began to call this pattern the “keyhole” tactic. For this method, groups post limited information about themselves and happenings online to tempt audiences to learn more, but none let the viewers into their space freely. In effect, audiences are looking through a keyhole into the room. The goal of the “keyhole” tactic is to convince interested parties to find the “key” (reach out to the group) and open the “door” (attend sessions and connect). Generally, researchers found the university groups heavily relied on this strategy for all events, while the other groups freely gave meeting places and times but were vague about attendees, conversations, and mid-event happenings.

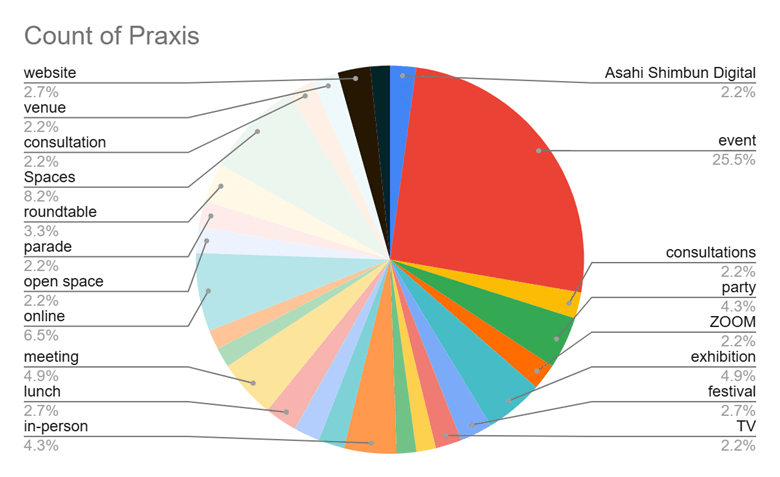

“Praxis”

It seems that trends from the 2010s largely hold true, there is an accelerated spatial relocation of groups to online, multi-platform focused initiatives.[21] Over the timeline of all data across groups, the biggest explicit mention of tangible communication mediums were various “events” (25.5% of mentions). Even when “events” were not explicitly mentioned, posts about multi-platform or in-person content were frequent, especially when groups wanted reactions. For example, Group B retweeted the following after the former aide Masayoshi Arai made disparaging remarks about queer people in February of 2023:

“[Urgent] Prime Minister Kishida met with LGBTQ-related organisations. What did the respective parties tell Prime Minister Kishida? What did the Prime Minister say? The debriefing will be urgently broadcast on YouTube Live from 22:30 tonight. I will be moderating. Please watch it. Watch▶️ [YouTube Live link]”

In this repost, Group B embeds a YouTube link and encourages cross-platform interaction. This example is exemplary of all groups’ habit of using X as an amplifier, or pipeline, for multi-media content/alternative resources, a trend researchers noticed early on. Returning to the original example, researchers noted that despite relatively high engagement (~550 likes, 250+ reposts, ~14,000 impressions), there was only one comment and it was left by the original poster. With similar pipeline-style posts, similar output was apparent. For example, an original post in September of 2024 from Group C about LINE consultations had ~202 impressions, but no other discernable interaction. Holistically, this clarifies that one-directional models of communication are the most common on X (with some exceptions) for the groups, and any feedback to outreach was taking place in contained, private spheres. Overall, X and other mediums serve to amplify these private events where more complete communication takes place.

“Kansai”

Within the entire “Kansai” mentions dataset, 51.3% were of “Group C.” “Osaka City” came in second with 17.8% of mentions and universities in Kansai aggregated to 16.4% of mentions. One reason for Group C’s preeminent position was due to its many collaborations, public events, and accessibility. For example, Group C posted in June of 2024:

“June’s ‘Pride Caravan Anywhere’ will visit [University Name]! 🚙🌈/ Date and Time: [June] Location: Space in front of the elevator on the 1st floor of Building D, [University Name]💡Free participation, come and go as you please💡Activities: Browsing LGBTQ books, chatting with staff, and more✨ Details here🔽 [Group C website link]”

In this post, Group C’s “caravan” event, a common pop-up around Osaka with attending Group C’s members, appears. The transient nature of the “caravan” events explains why Group C takes a majority of the location mentions, as it allows them to collaborate with other groups in the area and frequently publicize outings. Outside of the “caravan,” Group C also has a building. This stationary, legitimized location seems to attract many visitors, like Group A (who posted about going on December 19, 2023), and events, like from Group B (who uses Group C’s physical space frequently). It’s clear that Group C’s low barrier to entry, free educational materials, and continuous availability of staff make them and their resources central to other, less institutionalized, groups’ needs. In effect, Group C is operating at the center of the regional activist network, as a trusted resource and safe space.

Conclusions

At the beginning of this journey, researchers asked: What is the landscape of activism for contemporary young queer Japanese activists trending towards as online communication evolves? Throughout the study, it became clear that young people were tailoring their social spheres to their needs through online personalization. Observations showed emphasis on multi-generation inclusion, queer experience perspectivation, activism anchored by social protections, tactical inclusivity, multi-platform networking, and regional hierarchization. So, while this study is exploratory, there is much that can be developed on. Due to limitations of most resources, researchers were relegated to a ‘bare bones’-esque approach to data collection and analysis. With more funding, personnel, and time, future studies can surely expand on the new role hybrid realities are playing in evolving young deliberate socio-political activism. While researchers recognize the benefits of traditional ethnographic research and interviewing to understand community structure and strategies, further studies should focus more on the influence of online-based netnographic work as major events and digital platform normalization continue to filter people into online personas.[22]

[1]Carland-Echavarria, Patrick. “LGBTQ Activism in Contemporary Japan: Prospects and Perspectives Sustainability, Diversity, and Equality: Key Challenges for Japan, Springer, 2023, p.447-448; See also Boon, Emily. “Contemporary LGBTQ+ Politics in Japan,” 2025. p. 20.

[2] Doi-Benson, Anya. “The Assimilated Secret: Understanding as Silence in Japanese LGBT Discourse.” The Communication Review 27, no. 1 (2024): 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2023.2254171. pp. 86-89.

[3] Carland-Echavarria, Patrick. “We Do Not Live to Be Productive: LGBT Activism and the Politics of Productivity in Contemporary Japan.” Asia-Pacific Journal 20, no. 16 (2022): e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1557466022018708. pp. 12, 14-15, 17.

[4] Szeles, Cara. “Nailing down the Issue: How Japan’s 2023 Symbolic Reforms Fall Short and How the Japanese Government Can and Should Protect the LGBT Community through Proactive Lawmaking.” Va. J. Int’l L. 65 (2024): 165-166.

[5] Yomiuri Shimbun. Japan’s Teen Voter Turnout Remains Low at 43% in Recent Election; 18-Year-Old Women Had Highest Turnout Among Teen Voters. November 5, 2024. https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/election/20241105-220472/.

Tominaga, Kyouko. “Young People’s ‘Hate for Societal Movements’: The Source of Avoidance Towards Societal Movements.” Lifestyle Economic Policy: Youth and Politics Special Edition 288 (January 2021): 17–21.

[6] Kawano, Yuki. “Japan’s Births Mark Record Low in 2024, Plummet below 700,000.” The Asahi Shimbun, June 4, 2025. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15820762. Yamaguchi, Mari. “Japan’s Birth Rate Falls to a Record Low as the Number of Marriages Also Drops.” AP News, June 5, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/japan-birth-rate-declining-population-82662ea061286cb907fd7d071e5b0b9b.

[7] Braine, Naomi. “Sharing Information as Political Praxis among Activists for Self-Managed Abortion.” Radical Teacher, no. 129 (June 2024): 45–50. Alternative Press Index. pp. 46, 48; UNDP Istanbul Regional Hub. “Civic Participation of Youth in a Digital World: Rapid Analysis.” May 2021. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/eurasia/Civic-Participation-of-Youth-in-the-Digital-Word.pdf. p. 11.

[8] O’Day, Robin. “Differentiating SEALDs from Freeters, and Precariats: The Politics of Youth Movements in Contemporary Japan.” Asia-Pacific Journal 13, no. 37 (2015): e2. p.9

[9] Carland-Echavarria, Patrick. “We Do Not Live to Be Productive: LGBT Activism and the Politics of Productivity in Contemporary Japan.” Asia-Pacific Journal 20, no. 16 (2022): e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1557466022018708. pp. 12, 14-15, 17.

[10] Yamamura, Sakura. “Impact of Covid‐19 Pandemic on the Transnationalization of LGBT* Activism in Japan and Beyond.” Global Networks 23, no. 1 (2023): 120–31. Academic Search Premier. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12423. p. 121.

[11] Institute for Information and Communications Policy. FY2023 Survey Report on Usage Time of Information and Communications Media and Information Behavior. Ministry of Internal Affairs and for Communications, 2024. p. 10.

[12] Institute for Information and Communications Policy (2024).

[13] Cherry, Peyton. “Under Pressure and Voicing up: Japanese Youth Tackling Gender Issues.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford Online 15, no. 1 (2023). See also: Dale, Sonja Pei-Fen. “Teaching LGBT Rights in Japan: Learning from Classroom Experiences.” Human Rights Education in Asia-Pacific 7 (2016): 219–31.

[14] Doi-Benson (2024). p. 84.

[15]Yamamura (2023); Carland-Echavarria (2022); Doi-Benson (2024).

[16] Braine, Naomi. “Sharing Information as Political Praxis among Activists for Self-Managed Abortion.” Radical Teacher, no. 129 (June 2024): 45–50. Alternative Press Index. p. 49.

[17] Wallace, Jane. “Stepping-up: ‘Urban’ and ‘Queer’ Cultural Capital in LGBT and Queer Communities in Kansai, Japan.” Sexualities 23, no. 4 (2020): 666–82. Academic Search Premier. p. 21

[18] McLelland, Mark. “Beyond Common Sense: Sexuality and Gender in Contemporary Japan – Review.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, no. 10 (August 2004).

[19] To protect the identity of all subjects, identifying characteristics of example posts have been re-written with brackets to censor region descriptions and reflect aliases used within this essay.

[20] Jin, Dal Yong. “Platform Imperialism Theory From the Asian Perspectives.” Social Media + Society 11, no. 1 (2025): 20563051251329692. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051251329692.

[21] Yamamura, Sakura. “Impact of Covid‐19 Pandemic on the Transnationalization of LGBT* Activism in Japan and Beyond.” (2023) p. 121.

[22] We are excited to expand on all topics and more discussed here in our full-length report, as we hope this is simply the beginning of a larger conversation about youth LGBT activism.

Author Note

This is a preview of a full-report, and does not contain full analysis of the data.

Bibliography

Boon, Emily. Contemporary LGBTQ+ Politics in Japan: Policy Issues, Discourses and Developments, and the Role of Foreign Actors. Leiden Asia Centre, 2025. https://leidenasiacentre.nl/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/25-04-08-Contemporary-LGBTQ-Politics-in-Japan.pdf.

Braine, Naomi. “Sharing Information as Political Praxis among Activists for Self-Managed Abortion.” Radical Teacher, no. 129 (June 2024): 45–50. Alternative Press Index.

Carland-Echavarria, Patrick. “We Do Not Live to Be Productive: LGBT Activism and the Politics of Productivity in Contemporary Japan.” Asia-Pacific Journal 20, no. 16 (2022): e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1557466022018708.

Carland-Echavarria, Patrick. “LGBTQ Activism in Contemporary Japan: Prospects and Perspectives.” Sustainability, Diversity, and Equality: Key Challenges for Japan, Springer, 2023, 439–54.

Cherry, Peyton. “Under Pressure and Voicing up: Japanese Youth Tackling Gender Issues.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford Online 15, no. 1 (2023).

Dale, Sonja Pei-Fen. “Teaching LGBT Rights in Japan: Learning from Classroom Experiences.” Human Rights Education in Asia-Pacific 7 (2016): 219–31.

Doi-Benson, Anya. “The Assimilated Secret: Understanding as Silence in Japanese LGBT Discourse.” The Communication Review 27, no. 1 (2024): 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2023.2254171.

Institute for Information and Communications Policy. FY2023 Survey Report on Usage Time of Information and Communications Media and Information Behavior. Ministry of Internal Affairs and for Communications, 2024. https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/joho_tsusin/eng/pressrelease/2024/pdf/000382186_20240621_4.pdf.

Jin, Dal Yong. “Platform Imperialism Theory From the Asian Perspectives.” Social Media + Society 11, no. 1 (2025): 20563051251329692. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051251329692.

Kawano, Yuki. “Japan’s Births Mark Record Low in 2024, Plummet below 700,000.” The Asahi Shimbun, June 4, 2025. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15820762.

Mark McLelland, “Beyond Common Sense: Sexuality and Gender in Contemporary Japan – Review,” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, no. 10 (August 2004).

O’Day, Robin. “Differentiating SEALDs from Freeters, and Precariats: The Politics of Youth Movements in Contemporary Japan.” Asia-Pacific Journal 13, no. 37 (2015): e2.

Szeles, Cara. “Nailing down the Issue: How Japan’s 2023 Symbolic Reforms Fall Short and How the Japanese Government Can and Should Protect the LGBT Community through Proactive Lawmaking.” Va. J. Int’l L. 65 (2024): 159.

Tominaga, Kyouko. “Young People’s ‘Hate for Societal Movements’: The Source of Avoidance Towards Societal Movements.” Lifestyle Economic Policy: Youth and Politics Special Edition 288 (January 2021): 17–21.

Yamamura, Sakura. “Impact of Covid‐19 Pandemic on the Transnationalization of LGBT* Activism in Japan and Beyond.” Global Networks 23, no. 1 (2023): 120–31. Academic Search Premier. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12423.

Appendix A

Survey Questionnaire (Japanese and English[1])

Q1: 団体名

Q2: 団体の若者(18-29歳)の参加割合

Q3: 団体のミッション・ステートメント

Q4: 団体のアウトリーチの媒体(メディアなど)

Q5:若者に向けのイベント情報やアウトリーチなど、一例を教えてください。

Q5.1: いつされましたか?

Q5.2: どのようなメディアで行いましたか。

Q5.3: 作られた時、目的はなんでしたか。

Q5.4:この事例はどの程度効果的でしたか?

Q5.5:この例に基づいて、今後どうやってコミュニケーションを上達できるでしょうか。

Q6:現在行っている若者へのアウトリーチ活動に関して、一例を教えてください。

Q6.1: いつ始まりましたか?

Q6.2:どのようなメディアで行っていますか。

Q6.3:作られた時、目的はなんでしたか。

Q6.4:この事例はどの程度効果的だと思いますか。

Q6.5:この例に基づいて、今後どうやってコミュニケーションを上達できるでしょうか。

Q7:選んだ事例は、 団体における若者とのコミュニケーションの代表的なものだと思いますか?

Q7.1: その理由は何ですか?

Q8:団体によると、若者に向けのコミュニケーション方法に1~5の順位をつけてください。(1位が最も重要、5位が最も重要でない)

1. SNS

2. イベント

3. 雑誌や「ZINE」

4. ブログ

5. ポスターやイメージ

Q9:若者とのコミュニケーションにおいて、団体が直面している課題はあるでしょうか?この課題は、今後変化していくと思われますか?

Q10:該当する場合、団体はオンライン・コミュニケーション(SNS、ブログなど)に大きく依存していますか。

Q10.1:該当する場合、団体はいつからデジタル・コミュニケーションを利用していますか?

Q10.2 該当する場合、団体のデジタル参加はいつから始まりましたか。

Q1: Organization name

Q2: Organization’s estimate of general participation

Q2.1 Organization’s youth (18-29) participation

Q3: Organization’s mission statement or motivation

Q4: Organization’s mediums for outreach

Q5: Please provide one example of a successful outreach campaign to young people.

Q5.1: When did this happen?

Q5.2: On what medium?

Q5.3: Why was it created?

Q5.4: How effective was this example?

Q5.5: What would you recommend to improve future communications?

Q6: Please provide one example of a current outreach program to young people.

Q6.1: When did it begin?

Q6.2: On what medium?

Q6.3: Why was it created?

Q6.4: How effective has it been?

Q6.5: What would you recommend to improve future communications?

Q7: Do you think the examples you selected are representative of your organization’s communication with young people?

Q7.1:Why or why not?

Q8: Please rank from 1-5 how important each of these modes of communication are for your organization’s outreach to young people. (1st being most important to 5th being least important)

- SNS

- Live events

- Magazines

- Blog

- Posters

Q9: What are some challenges your organization faces in youth communication? Will these challenges change in the future?

Q10: If applicable, does your organization rely heavily on online forms of communication (i.e., SNS, blogs, etc.)?

Q10.1 If applicable, when did your organization start using digital communications?

Q10.2 If applicable, when did your organization start relying on digital participation?

Appendix B

Visuals of Concept Mentions[2]

[1] English version is for reference only. Japanese version was sent to groups.

[2] Other charts and data will be made available upon request and within the full report.

Biographical Note(s) of the Author(s)

Sophia Isaacson is USA Pavilion Youth Ambassador for the 2025 Osaka Expo. She graduated summa cum laude from American University and Ritsumeikan University in 2024. Recently, Sophia was inducted into the national academic honors society, Phi Beta Kappa. She has previously spent time as an assistant managing editor for the American University’s undergraduate research journal, Clocks and Clouds, and has gained professional experience in settings like the U.S. House of Representatives, Library of Congress, U.S. Census Bureau, Pennsylvania Superior Court, and more.

Logan Day is a Youth Ambassador at the USA Pavilion for the 2025 Osaka Expo. He graduated in 2024 with a dual degree in international relations from American University & Ritsumeikan University. He also executed Japan’s first study of university student hunger which he presented in the 2024 International Conference on Human Rights: Youth in Asia. Logan wrote his thesis on international LGBTQ community activism and development in Japan. His work and volunteering focus on empowering young people, and creating more equitable, sustainable, and healthy communities.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Share this article